I know it’s not fair, but I consider a person’s opinion on dogs a litmus test for who they are, one any visitor to our house undergoes

We have two dogs in our family. Laurel is a rescue so stunningly beautiful that strangers stop me to ask where she came from. Colored like a Foxhound and sized like a Great Pyrenees, her forebears who crossed paths somewhere in south Georgia, she was supposed to weigh fifty pounds, a prediction as accurate as the rescue organization’s claim that she is a “Labrador mix.” She’s ninety-five pounds of double dew claws and coal-rimmed eyes gazing out from above a long nose so effective I can hear it thumping like a bass drum when she’s drinking deep of a scent trail. Laurel’s main job is ensuring whatever she chooses to lie upon doesn’t go anywhere. It’s a right she’s earned with her repeatedly demonstrated willingness to put herself between threats and the people she and I most love. She’s killed a rabid fox in our yard and put paid to a coyote who got too close to my daughter. I would clone her if I could.

But as much as I love our lay-around dog, I am a waterfowl hunter, and a Labrador retriever pounding through chest-deep water at my command, in pursuit of fallen ducks, prismatic explosions of sun-struck water all around, stirs my heart and assures me that there is something akin to divinity in the relationship between humans and dogs. Of course, that is an idealized vision of a gun dog. We live within their reality which is that, while working with a gundog is one of the single most rewarding experiences I have ever had, for a novice like me, life with my Labrador Jed is a constant state of anxiety and problem-solving.

My great-grandfather was a dog man from Union Springs, Alabama, the son and brother of men for whom dogs and quail were their lives. They ran dogs bred for indefatigability and drive. Those are admirable qualities in a retriever as well, but the difference in purpose is where my devotion to retrievers is found. A Tallahassee plantation manager and kennel owner said to me, “A pointer hunts for himself, a retriever hunts for you.” In no dog I’ve ever had is that truer than my Labrador Jed.

I am inordinately proud of the work we have done over almost four years together. Jed’s body almost audibly hums as he waits at heel, exploding at the command to grab bird or bumper. He takes “over” and “back” commands perfectly and will predictably take an angle cast about 70% of the time. One hundred yards out, he will find a bird or wear himself out trying. Any failures are mine.

But Jed has a challenge. Rock steady to shot when he came home from four months with Bill Mattes, we hunted his first year without issue. But three successive summers of explosive thunderstorms have since left him less than enamored of loud noises. It’s an issue that could mean the early end of a hunting career for a dog less driven to please. Jed still brings ducks to hand, but keeping him there requires constant work. In that, I’ve found one of many life lessons he’s taught me: Life with a gundog is not one of reached destinations, it is one of side roads and detours and the occasional dead end. It is trial and error and constant work. I suspect there is a broader lesson about our own lives there.

Fortunately, I love the work. Alone or with my friends Henry and Hector and their Labs, Isla and Ruby, Jed and I are regularly in the woods, water, and fields. When I need authoritative advice, generous experts like Mattes and Grayson Guyer are there for us. I find that to be true of gundog lovers generally.

Henry’s Isla is a Wildrose Carolinas dog. I’d read Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dog and Retriever Training the Wildrose Way and driven by Wildrose Carolinas countless times when I met co-owner Kirk Parker at the Southeastern Wildlife Exposition in Charleston. Parker invited me to Mebane, but I’d never visited until a recent day when Jed and I accompanied Isla and Henry to Mebane, North Carolina, for a day on the Wildrose property. It is 250 acres of ponds and a lake among rolling hills cut by trails and fields, the Magic Kingdom for Labradors.

My visit to Wildrose also allowed me to chat with co-owner Steven Lucius and Head Trainer Chris Torain about Jed. Torain owned and loved a Bill Mattes Labrador, something we have in common, and which made it easy to sit in rocking chairs, surrounded by well-mannered Labs, and discuss things I’ve done well and things I’ve not. Torain said something I’ve long suspected but needed to hear from an authority: “Sometimes you have to create a problem to solve one.”

There’s a universal truth in that statement, about prioritizing issues in our lives, fixing the big ones before worrying about lesser things that may have arisen in the process. There’s also a message about acceptance. Last year, except for one day, I did not pull a trigger in a duck blind or even carry a shotgun. Concealed in brush or a flooded corn field, Jed and I sat off to the side, focused solely on retrieving for others, associating the reward for Jed’s drive with gunfire. It was a detour on the road to what I thought was our ultimate destination: me hunting ducks with a Labrador by my side, his imagined robotic perfection a proxy for my ego. But I’ve since realized I reached my destination a long time ago. I wanted to earn a dog’s dedication and loyalty through hard work. I wanted to accrue some understanding of the kind of skills with which my great-grandfather made his living. I wanted to experience the joy of connecting with a dog in a way beyond treats and belly rubs. We’re there; the rest of it is just detours and byways.

That’s life, I reckon. We think in terms of optimums but live in terms of realities. If we are lucky, along the way we find a dog who will give us all his latter in pursuit of his former. By that measure, Jed is perfect. I just had to learn enough from him to appreciate it.

Yours,

Russell Worth Parker

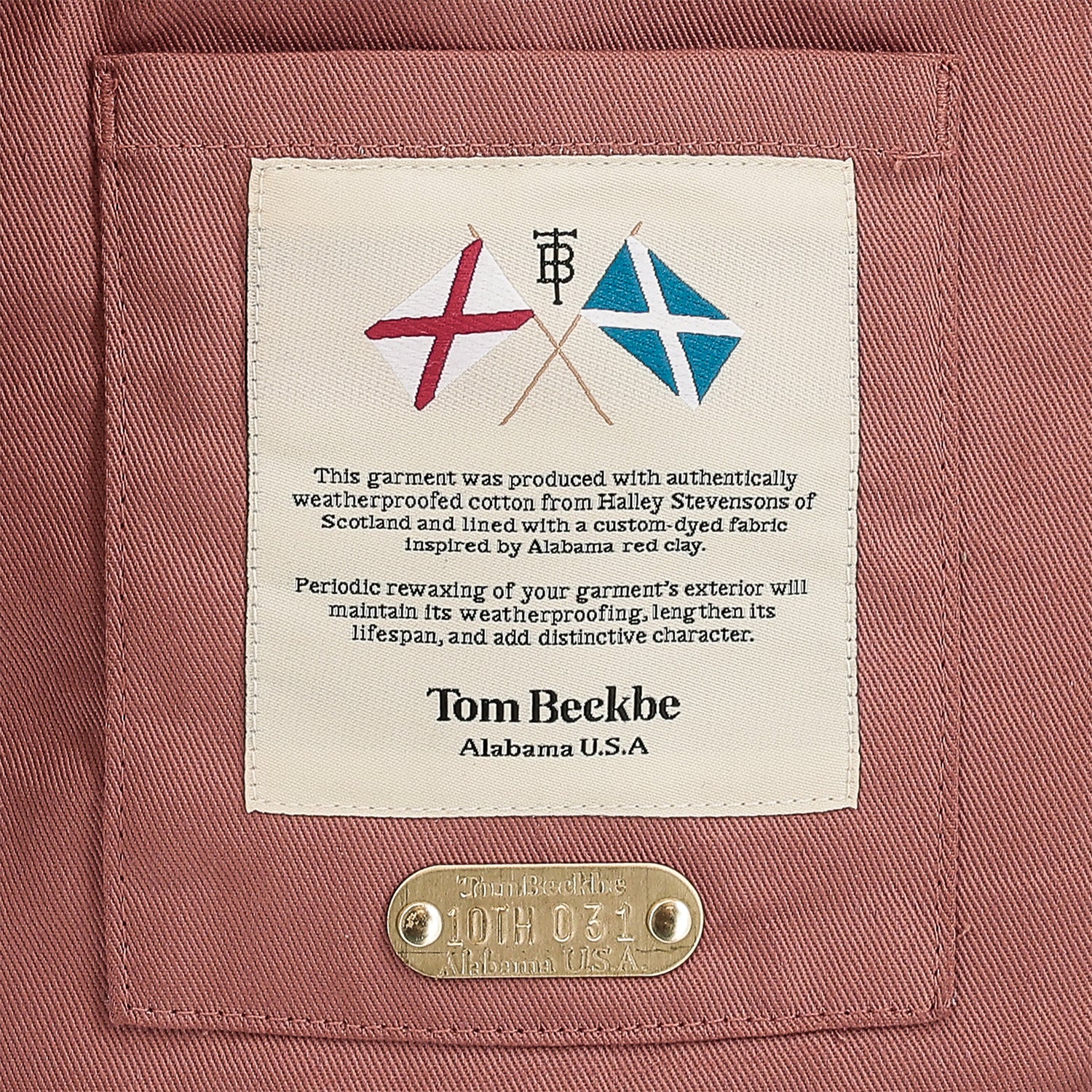

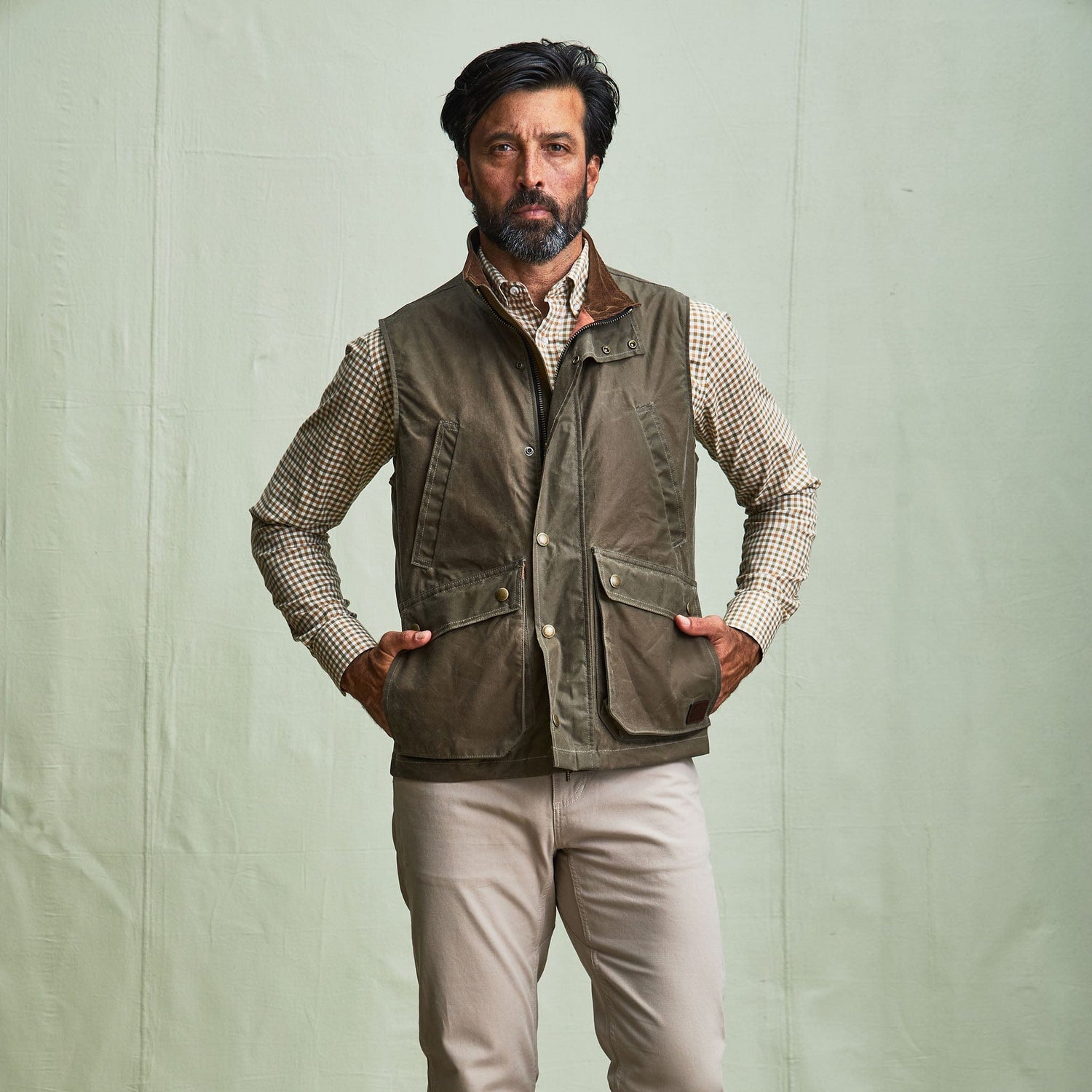

Editor-in-Chief, Tom Beckbe Field Journal