The doe came in quickly, leaping over a small creek and pushing through a narrow trail in the rhododendron, bothered by a small buck sixty yards behind her. He was following her scent, over eager and persistent. She stopped in front of my tree stand, broadside, her head behind a mature pine, looking over her shoulder to see if she had lost her pursuer. I released the bow string and heard her fall on the rocks a short distance away from where the arrow pierced her heart. I was grateful for her life and the meat she would provide. In the way old hunters sometimes are, I was moved by her death and the loss I felt.

I climbed down and opened my backpack to get to the tools to field dress her, removing my copy of Ivan Turgenev’s Sketches from a Hunter’s Album laying atop the gear packed for my day in the woods.

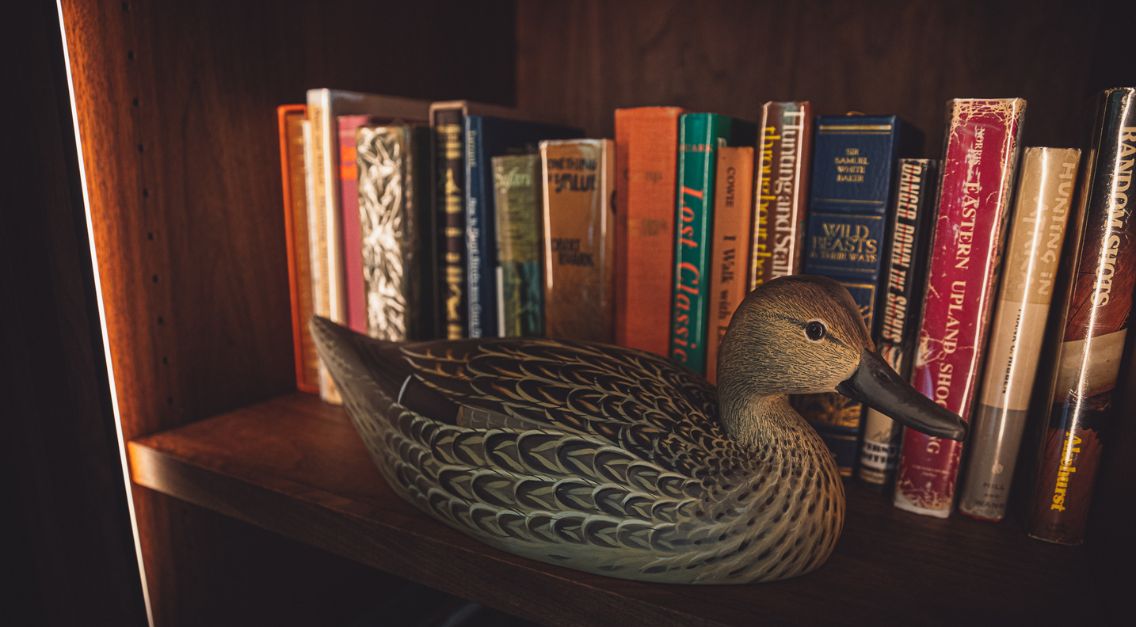

The book was in poor condition; scarred by travels in ruck sacks, blind bags and game pouches. I’ve read it in drizzling rain and snow, forests and swamps, mountains and high desert, in deer stands and duck blinds, and sitting in the dirt with my back against a white oak tree, a squirrel rifle across my knees. It is coffee, blood, and mud stained and held together with packing tape. A friend, observing my battered copy in a tent we shared, remarked that I shouldn’t be allowed to own books.

The best of my books are trashed.

Each time I reread Turgenev, often before and during hunting season, I confirm the last part of Heraclitus’ dictum “No man ever steps in the same river twice. For it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” I find importance and insights in different passages and different characters, for I’m “not the same man.” I hope that I’m a better man, gentler and more forgiving of the world, influenced in some small way by the author. I’ve undoubtedly gained experience between readings and might have gained some wisdom, but under oath would have to admit there is little evidence of this.

I came across Sketches from a Hunter’s Album in a used bookstore across from Harvard University. The store benefitted from its proximity to the school. The shelves were stocked with books from professors retired, downsized, or recently dead, the bereaved family finding the location convenient for converting their departed loved one’s burdensome belongings to cash. The improbably large section of hunting books was filled with the best outdoor literature ever written. The store closed years ago. I still remember how it smelled.

I bought the book because of the three-dollar price written lightly in pencil on the inside cover, it was about hunting, and I was young and broke. I didn’t know it would change me, or that it had a hand in changing the course of history.

I’m not alone in my admiration of Turgenev. Ernest Hemingway first came across Sketches from a Hunter’s Album at Shakespeare and Company, the English-language bookstore and gathering spot for “The Lost Generation,” when he arrived in Paris. He later remarked that he considered Turgenev “the greatest writer there ever was.”

Ivan Turgenev was a nineteenth century Russian novelist and hunter. Sketches From a Hunter’s Album was his first major work. In it, the narrator (a thinly veiled version of the author) travels the countryside hunting and observing the people who inhabit the vast estates held by the nobles of the time. Many of the people Turgenev’s proxy writes about are serfs, peasants attached to the lands of Tsarist Russia’s nobles. They could be bought and sold along with the land, had no rights to speak of, and were captured and severely punished if they tried to leave. In the middle of the nineteenth century over a third of the Russian population were serfs. Turgenev’s descriptions are poignant, beautiful and often funny. Each story illuminates the characters he encounters, acknowledging their dignity and humanity without idealizing them. It is warm and empathetic, lacking in condescension.

He was less generous with the nobles. His ability to discern their motivations and conceits, their foolishness and self-importance was often cutting and hilarious. Turgenev, a noble himself, was strongly opposed to serfdom and his writing was an effective tool in securing their freedom. Some say that when Tsar Alexander II read The Hunting Sketches, he was moved to free the serfs.

Politics, history and human motivations are rarely that simple. I tend to side with historians who argue that the Tsar was looking for an excuse to end serfdom, long past the time when he should have acted, and used the popularity of the book as an excuse to overcome the objections of the nobles. Whichever version is closer to the truth, Sketches from a Hunter’s Album played an important role. Turgenev wrote a hunting book that changed the course of world history. Like many of the best hunting books, it was about what it meant to be human.

I cleaned the doe’s blood from my hands and knife in the small stream, promising myself to remember to take off my watch the next time I field dressed a deer. Packing up in preparation for the steep uphill drag ahead of me, I placed the The Hunting Sketches back in my pack, another bit of blood, a smear of dirt, upon it.

Note:

There are a few English translations of this book including: Sketches from a Hunters Album, A Sportsman’s Sketches, A Hunter’s Sketches, and A Sportsman’s Notebook.

Every translation is worth reading, but A Sportsman’s Notebook is worth reading for the preface alone.

About the Author

David LaMere is the host of The Wild Huntsman Podcast. He enjoys hunting and overthinking things. He may be found on Instagram at @thewildhuntsmanpodcast.